David Lynch is that rare artist who unites traditions, often apart or at odds with what is thought to be traditional narrative and avant-garde film. Lynch’s fine arts background, attending art school in Philadelphia as an aspiring painter, spurred him into filmmaking by a desire to see his paintings move, and his first efforts were distinctly in the experimental vein. As proven by Twin Peaks: The Return, the same spirit remains alive in Lynch—for proof, look no further than Episode 8, a tangled, visceral multi-megaton blast of invention that brought together personal cosmology and postwar history in a single bravura performance. While The Return continues to unfold, Metrograph selected a program of Lynch’s more far out productions, alongside a collection of films—many non-narrative—that complement or inform his work.

2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick/1968/149 mins/35mm)

A mind-bending, epoch-hopping opus that set the bar for philosophical, historical, and cinematic ambition. Without Kubrick’s masterpiece, it’s impossible to imagine the grand design of Twin Peaks: The Return, situating their human-scale stories within a framework as large as the universe itself. A campus circuit phenomenon which motivated multiple viewings, and considered best enjoyed with chemical assistance (“The Ultimate Trip”), 2001 laid the foundation for the soon-to-be-named Midnight Movie, which Eraserhead would come to define.

Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (David Lynch/1992/135 mins/DCP)

Scorned on initial release, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is widely pointed to as the dark, beating heart of Lynch’s art. Set in the week before the events depicted in the original television series, this prequel follows the doomed Laura Palmer, the familiar denizens of Twin Peaks, Washington, and a beefed-up cast that includes David Bowie, Harry Dean Stanton, and Heather Graham. Both an expansion and a distillation of the series, which burrows into its core of implacable sadness and pain.

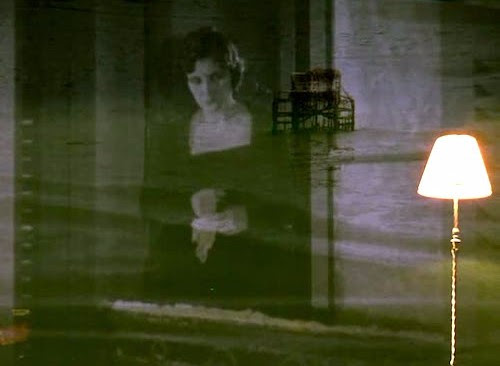

Eraserhead (David Lynch/1977/89 mins/35mm)

The ne plus ultra of midnight movies, at once enormously influential and inimitable. A pompadoured Jack Nance plays henpecked Henry, a miserable, furtive figure traversing a clangorous industrial landscape whose nights are made interminable by the incessant squalling of his mutant baby. Funny, frightening, and unforgettable, Lynch’s years-in-the-making first feature is like a volcanic eruption of dormant creative energy. “Not a movie I would drop acid for, although I would consider it a revolutionary act if someone dropped a reel of it into the middle of Star Wars.” - J. Hoberman

Stalker (Andrei Tarkovsky/1979/163 mins/DCP)

When reference is made in Twin Peaks: The Return to “The Zone,” it seems an awful lot like a homage to Tarkovsky’s stunning, haunted sepia-toned sci-fi masterpiece, in which a scientist and a writer living in a broken-down totalitarian dystopia recruit the help of a “Stalker”—a kind of post-apocalyptic Sherpa—to guide them on a voyage of self-discovery, passing through the bleak, otherworldly Zone, hoping to discover therein a haven that will fulfill their secret desires.

Kiss Me Deadly (Robert Aldrich/1955/106 mins/DCP)

Lynch most overtly paid his respects to Aldrich’s va-va-voom hard-boiled doomsday noir with the burning beach bungalow of Lost Highway, but its influence can also be found in Twin Peaks: The Return, another mystery on the trail of “The great whatsit” firmly situated under the cloud of nuclear paranoia. With Ralph Meeker playing Mickey Spillane’s he-man gumshoe Mike Hammer as an unprincipled thug, rampaging through Los Angeles on the trail of a device that threatens Armageddon. Restored version with original ending preferred by Aldrich.

Radio Bikini (Robert Stone/1988/60 mins/DCP)

Through archival footage (much of it never before seen by civilians), fragments of an incomplete government propaganda film, and the testimony of firsthand witnesses, Stone’s Oscar-nominated documentary tells the story of Operation Crossroads, the first nuclear weapons test by the United States, conducted at Bikini Atoll in the summer of 1946—an event which would lend its name to a women’s two-piece swimsuit, and incontestably secure us in the Atomic Age.

Shorts Program #1

Serene Velocity (Ernie Gehr/1970/23 mins/16mm)

Water and Power (Pat O’Neill/1967/57 mins/35mm)

Garden of Earthly Delights (Stan Brakhage/1981/3 mins/16mm)

Infinite Doors (Takeshi Murata/2010/2 mins/DCP)

Cosmic Ray (Bruce Conner/1962/4 mins/16mm)

As Lynch revels in doorways to other dimensions, this program is linked, literally, by passageways and entrances—the game show prize reveals of Murata’s Infinite Doors; the burrow through tortured vegetation in Brakhage’s The Garden of Earthly Delights; the diagetic ruptures of Conner’s Cosmic Ray; the strange traversing of the basement corridor of SUNY Binghamton in Gehr’s Serene Velocity; or the complex optical prints that make up O’Neill’s Water and Power, which charts the rise of the Los Angeles metropolis from the barren desert wastes.

Shorts Program 2

History (Ernie Gehr/1970/25 mins/16mm)

Trouble in the Image (Pat O’Neill/1996/38 mins/35mm)

World Shadow (Stan Brakhage/1972/3 mins/16mm)

Pink Dot (Takeshi Murata/2007/5 mins/DCP)

Mothlight (Stan Brakhage/1963/4 mins/16mm)

A sense of secret history runs through Lynch’s work, and this collection prods the scars of a turbulent past through images of tumult and chaos. Brakhage’s decoupages roil and rumble; Gehr’s History works without a camera lens, exposing film through black cheesecloth, achieving simmering visuals; O’Neill uses found footage and an optical printer to discover Trouble in the Image; while Murata digitally manipulates Rambo: First Blood (1982) into a hypnotic abstraction.

Shorts Program 3

Untitled (Silver) (Takeshi Murata/2007/11 mins/DCP)

Krypton Is Doomed (Ken Jacobs/2005/34 mins/DCP)

Epileptic Seizure Comparison (Paul Sharits/1976/30 mins/16mm)

Owl Gets in Your Eyes (Chris Marker/1994/1 min/DCP)

Breakaway (Bruce Conner/1996/5 mins/35mm)

A headlong plunge into the woods—both the mystery and majesty of nature, and the thickets of a frame choked in overgrowth. The owls are not what they seem for Marker; Murata uses digital processing to create a forest of black-and-white from Mario Bava’s Black Sunday (1960); Jacobs matches audio from the first Superman radio broadcast to visuals from one of his “Nervous Magic Lantern” performances; Sharits attempts to mimic the conditions of epilepsy through convulsive light and sound; and Conner singlehandedly invents the music video in Breakaway (Starring Toni Basil!)

Shorts Program 4

Outer Space (Peter Tscherkassky/1999/10 mins/35mm)

Bi-Temporal Vision of the Sea (Ken Jacobs/1994/20 mins/DCP)

Arnulf Rainer (Peter Kubelka/1960/7 mins/35mm)

Mongoloid (Bruce Conner/1978/4 mins/16mm)

Crossroads (Bruce Conner/1976/36 mins/35mm)

The mythology of Twin Peaks now stretches all the way back to Los Alamos, and this assembly of films explore, overtly or otherwise, the terrible beauty of the Atomic Age and hostile, even apocalyptic landscapes. Conner devolves with Devo and gazes upon blossoming mushroom clouds at humanity’s Crossroads; Tscherkassky’s Outer Space designs a seething, hostile environment from a Barbara Hershey movie; Jacobs sets sail on a strobing Bi-Temporal Vision of the Sea; a two-tone film that looks positively colorful next to Kubelka’s stark, suttering Arnulf Rainer. |

No comments:

Post a Comment